Welcome to Florida—Please Don’t Believe Everything You Hear

Florida Wildlife: Separating Facts From Fear

Florida is a place where stories spread faster than mosquitos in July. Ask any longtime resident and you’ll hear at least one dramatic tale about snakes “chasing” people, owls stealing pets, or raccoons turning rabid the moment the sun comes up. These stories are memorable, easy to repeat, and often passed down for generations — but most of them have very little to do with how wildlife actually behaves. Misconceptions about animals can do real harm. They can cause people to panic when they don’t need to, misidentify normal behavior as dangerous, or take actions that endanger wildlife unnecessarily. They also create fear where understanding should be — and fear is one of the biggest drivers of conflict between humans and the animals that live around us.

Florida’s wildlife isn’t out to get us. In fact, many of the species people worry about the most are shy, avoidant, and just trying to survive in habitats that get smaller every year. By breaking down some of the most common myths, and replacing legend with science, we can help people feel safer, protect local wildlife, and reduce the kinds of avoidable incidents that fill rehab centers every day.

Below are some of the biggest wildlife misconceptions that continue to circulate in Florida to this day, and the real behaviors behind them.

Misconception #1: Snakes are aggressive and will chase you.

Truth: Snakes do not chase humans. In reality, they flee, hide, or remain still when encountered. According to the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS), the vast majority of snake-human encounters involve non-venomous species, and occur because the snake is startled or cornered. When threatened, snakes may flatten their bodies, hiss, or strike if unable to escape, but these are last-resource defenses, not predatory behavior. UF/IFAS notes that believing a snake will actively hunt or chase people leads to panic, irrational responses, and increased risk for both humans and the snake. Snakes are much more afraid of humans than we are of them, and in a panicked effort to escape your presence, may poorly choose an escape route, resulting it them moving toward you. They are not chasing you, they are just exercising poor judgement in a moment of fear. In Florida, the principle of giving snakes space and not provoking them is emphasized repeatedly by professionals. If you cross a snake in your path, leave the area for a few minutes, and it is very likely the snake will have disappeared by the time you return.

Misconception #2: An animal out during the daytime has rabies.

Truth: Daytime wildlife sightings are not a reliable indicator of rabies. Many Florida species are naturally diurnal or crepuscular (meaning they are most active dawn/dusk) and may be seen in daylight for normal reasons such as feeding young, moving between habitats, or escaping predators. According to the Florida Department of Health, the primary wildlife rabies carriers in Florida include raccoons, bats, skunks, foxes, and coyotes. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) adds that while bats do carry rabies, only about 6 % of submitted bats test positive, and healthy colonies typically show far lower incidence. Misinterpreting daylight wildlife activity as rabies leads to unnecessary fear and potentially harmful actions (for example, killing an animal when it is healthy) rather than responsible avoidance and reporting.

Misconception #3: If a baby animal is alone, it’s abandoned.

Truth: In Florida’s wild, many young animals are left alone for extended periods while their parents forage, rest, or avoid predators. For example, fawns are left hidden in tall grass, bird fledglings may hop around while their parents bring them food, raccoon kits often play and explore while their mother is supervising nearby, and more. Intervening prematurely by picking them up, relocating them, or “rescuing” can actually decrease survival. The parent may be just out of view, or return later, to find their babies missing. This misconception often leads well-meaning people to remove healthy wildlife, which can overwhelm rehab centers, and become detrimental to the animal they are attempting to save.

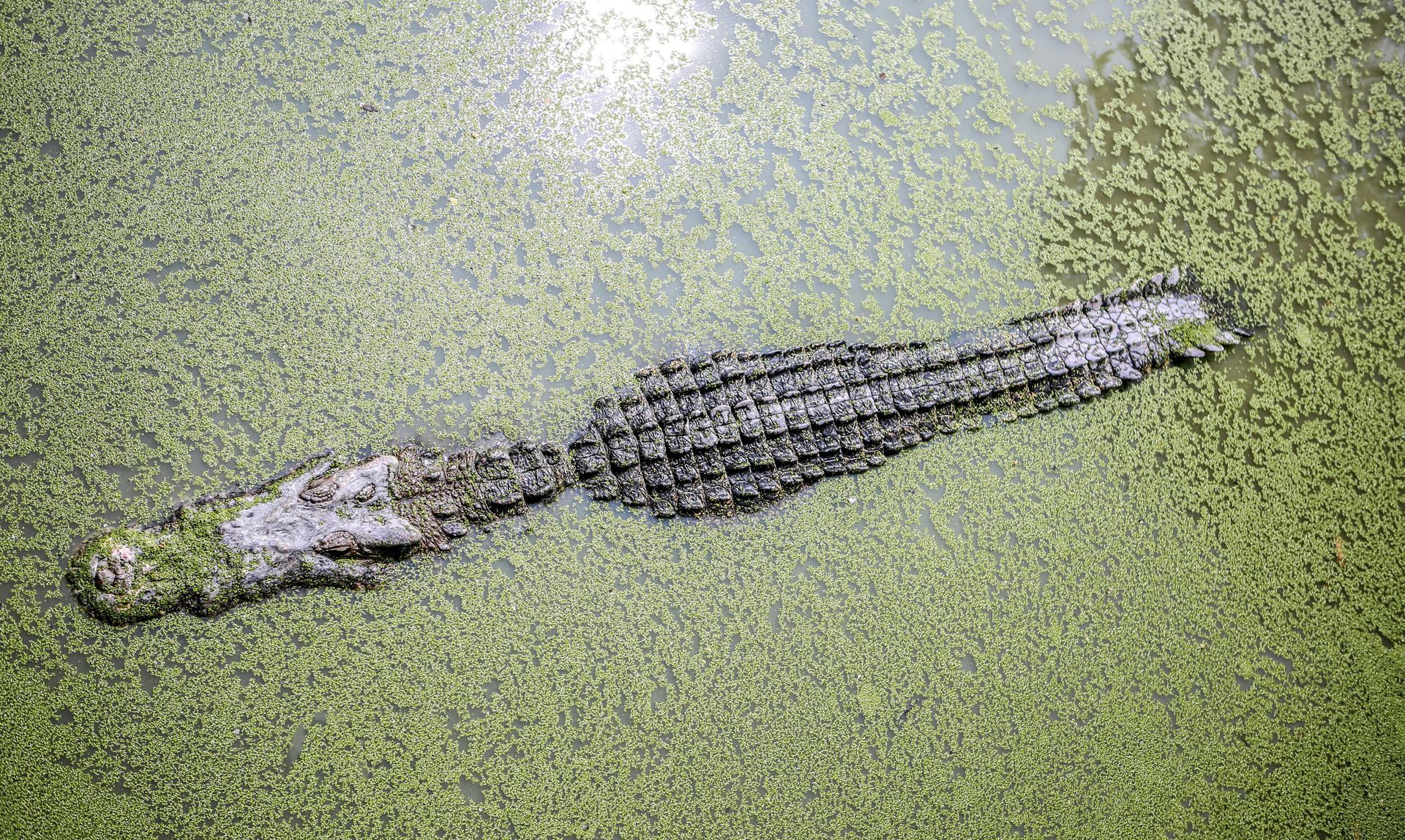

Misconception #4: Alligators are just waiting to attack people.

Truth: While the American Alligator is capable of attacking humans, fatal human-alligator encounters in Florida are rare. Gators are generally shy and try to avoid people. Many so-called “aggressive” alligator incidents occur because the animal has been fed (and humanized as a result), or when a pet is near water, or a person approaches too closely and harasses the animal. Respecting water-edge boundaries, not feeding wildlife, and keeping pets away from shorelines reduce the likelihood of conflict. Virginia Tech, wildlife agencies and Florida’s own data support this—hundreds of millions of people recreate around Florida waters annually, while the number of fatal attacks is in the tens over decades.

Misconception #5: All bats are rabid and want to swoop at you.

Truth: While bats are rabies vector species (RVS), the risk is lower than most people realize. FWC states that in healthy Florida bat colonies, less than 1 out of every 20 bats has rabies. In fact, bats are insect-eating, nocturnal mammals that avoid humans and do not intentionally swoop at or chase people. Myths that they will dive into hair or aggressively attack humans are completely unfounded. Bats have poor eyesight, and a naturally erratic flight pattern, making it seem as through they are diving at people. Most bats encountered during the day or in odd places are disoriented, injured, or roosting—not rabid attackers.

Misconception #6: Bobcats and coyotes will stalk or attack people.

Truth: Both the Bobcat and the Coyote can be found increasingly in suburban Florida. According to FWC, coyotes have been documented in all 67 Florida counties and have adapted to human-dominated habitats. However, unprovoked attacks on people are very rare. The same article states that most encounters occur because coyotes have been fed or have become habituated to people. Predation on pets (especially small dogs or cats let out at dusk/dawn) is possible, yet human attacks remain statistically minimal. The fear that these animals are lurking and ready to pounce on children playing in the yard or walking to the bus stop doesn’t reflect the science—these predators avoid humans unless conditioned to expect food. Both bobcats and coyotes are naturally fearful as well, and something as simple as a motion-activated floodlight, a whistle, or even just clapping or yelling, will scare them off.

Misconception #7: Raptors want to eat your pets (and they often will).

Truth: Florida’s birds of prey, such as hawks, owls, or eagles, are skilled hunters, but they are not adapted to regularly take down animals the size of most household pets. Even the largest raptors are far lighter than most people realize. A full-grown Bald Eagle weighs only 6–14 pounds, a Great Horned Owl averages 3–4 pounds, and most hawks weigh under 2 pounds. Raptors cannot safely subdue prey heavier than themselves without risking serious injury to their wings, feet, or internal organs, and would have a hard time carrying that prey off. Because most cats and small dogs weigh 8–15 pounds, they are simply too large and too strong for a raptor to target. When raptors perch in yards or watch from rooftops, they are almost always looking for their actual prey: rodents, snakes, lizards, rabbits, fledgling birds, or squirrels. Rare incidents involve extremely small animals (usually under 1-2 pounds) that resemble natural prey in size and movement, and even those cases are uncommon. The popular idea that hawks or owls “circle neighborhoods looking for pets to steal” stems from viral videos, dramatic news stories, and repeated myths—not real wildlife behavior. Raptors play a crucial role in rodent control and environmental balance, and simple precaution, such as supervising small pets outdoors and removing outdoor food sources, are usually all that’s needed to prevent conflict.

Why This Matters

Misconceptions about wildlife lead to fear, unnecessary removal or harm of animals, and missed opportunities for coexistence. For your part as a resident, homeowner, or nature-lover in Florida, knowing the truths helps you act wisely: don’t assume danger where none exists, protect yourself and your pets where real risk lies, and support responsible wildlife recovery and habitat efforts.